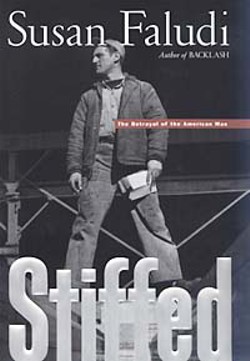

Susan Faludi’s book “Stiffed: The Betrayal of the American Man” takes a remarkably compassionate and revealing look at the crisis of modern masculinity from a feminist prospective. Faludi is an award-winning writer with the skills required to make a challenging topic easy reading. The book is based on years of fieldwork among men involved in various efforts to recreate some kind of a manly world for themselves. Using WWII as a starting point she goes on to shipyards, the space program, the Citadel, football fans, the New Left, Vietnam War, militias, Waco, gangsters, Promise Keepers, porn stars, the Gay liberation movement and more.

It’s all incredibly interesting and often surprising. Almost all of these attempts fail and far too many of these men pointed to feminism as the problem. The real causes of the crisis in masculinity lie in deeper personal and political changes far harder to understand or admit to.

For Faludi that crisis for male identity begins after WWII when an earlier masculinity grounded in being the family breadwinning, community service, useful work, care and nurturance was undermined. The rise of the new corporate consumer culture changed the way work was done and war’s were fought — sealing the fate of older masculine ideals.

This new economic regime undermined traditional masculinity by demanding obedience and passivity. In consumer culture, the pretty and ornamental were all that mattered. Mass media culture valued image over substance and celebrity over daily acts of service or useful work. Feelings mattered most while action was discouraged.

The only way for men to achieve recognition in consumer culture was for them to adopt the behaviors of a conventional femininity already widely critiqued and opposed by feminism. So whether men attempted to recreate conventional masculinity or adapt a more consumer-culture friendly version—based on image alone— they had a gnawing sense of failure. There was no longer a clear answer to the question: What does it mean to be a man? The search for masculinity lead to a dead end and we are still lost.

In the face of this dilemma the fathers of the 50’s and 60’s had little to pass on to their sons. Many of the men interviewed in this book experienced the crisis of masculinity as a heart-breaking and very personal failure. Those seeking masculine comforts in the projects and movements Faludi investigates did not have much of a relationship with their silent or absent fathers — who in the end were as overcome by the crisis in gender as they were.

Second Wave Feminism was triggered, in part, by mass resistance against the suffocating expectations of gender roles. The author rightly asks why men did not revolt against their gender expectations as well since we were stuck in the same restricted gendered universe. Faludi answer is, of course, incomplete. But we should accept the evidence that existing strategies of social movements have proven incapable of launching a massive men’s movements based on challenging established gender roles.

And while the way forward remains unclear Faludi does give us two very helpful goal posts. The first suggests a transformative approach beyond masculinity.

“Because as men struggle to free themselves from their crisis their task is not …to figure out how to be masculine—rather, their masculinity lies in figuring out how to be human.”

Now that is useful work befitting a real man.

The second thing Faludi suggest is to focus on action; on doing. Quoting Sylvester Stallone, of all people, she wrote:

“So I’m going to put away this vanity and get on with my life. I don’t even think about what I look like. I think about what I have to do not what I look like when I’m doing.”

We can become better men not by chasing after some mystical male identity or gazing at our own reflections but by finding useful things to do. We are what we do — not an identity we claim to be.

So what should we do? I wish I knew. But If we take some cues from a similar struggle the road ahead might become just a little easier to see. I am thinking of the struggle against “whiteness” that white people must undertake. Since men and white people remain as two large buffer groups standing between the tiny elites and the discontented millions, freeing ourselves from this role may well be decisive. Since men and white people are the two largest categories of “house servants” — of everyday people that tend to identity with the powerful — maybe there are some hidden synergies we can learn from. Both are best addressed by doing and acting.

First things first, we should organize men to join the great struggles for freedom that lie ahead. And we must embrace a very simple compelling truth: there will be no freedom for any of us as long as patriarchy and male dominance holds down half the world. Those ideas are getting weaker by the year. It’s hard to miss the leading role of women and girls in the historic West Virginia teachers strike, in the youthful struggle against gun violence, in the new civil rights movement, and, of course, in #metoo.

We need to consider a less simple truth as well: masculinity and male privilege holds men down and keeps us in our places. Yes, we can lord it over those “below” us — but at a price: we agree not to rebel against those “above” us. But it is in that rebellion we can find ourselves, our freedom and take our rightful place in the world.

So men — help other men get active. Anyplace is a good place to start. When the day finally comes that our activism has changed us so deeply that white people no longer act white all the time and men no are longer obsessed with achieving masculine ideals that we will at long last discover our humanity and stand on the threshold of fundamental social change.

Good job. For some of us the women’s movement made it possible to imagine another way of being a man than that of our fathers and grandfathers, even if imperfectly. For that we should show great gratitude. i try to myself.

LikeLike

Indeed. Feminism opened the door. Now can we walk thru it?

LikeLike